- Home

- Pietrzyk, Leslie

This Angel on My Chest

This Angel on My Chest Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Contents

Ten Things

Acquiescence

A Quiz

Heat

In a Dream

One Art

Do You Believe in Ghosts?

Slut

I Am the Widow

One True Thing

Someone in Nebraska

What I Could Buy

Truth-Telling for Adults

Chapter Ten: An Index of Food (Draft)

The Circle

Present Tense

Acknowledgments

DRUE HEINZ LITERATURE PRIZE

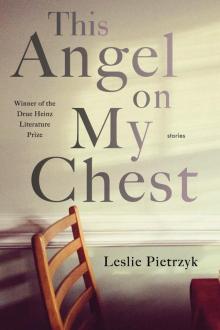

This Angel on My Chest

Stories

Leslie Pietrzyk

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PRESS

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The following stories have been previously published: “Ten Things,” The Sun, and reprinted in The Mysterious Life of the Heart, edited by Sy Safransky (North Carolina: The Sun Publishing Company, 2009); “Acquiescence,” Shenandoah; “Slut,” Cimarron Review; “I Am the Widow,” r.kv.r.y; “One True Thing,” The Collagist; “Someone in Nebraska,” Potomac Review; “What I Could Buy,” Hobart; “The Circle,” Gettysburg Review. A section of “One Art” was performed at Story League: Sophomore Outing, May 2011, Washington, DC.

Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA, 15260

Copyright © 2015, Leslie Pietrzyk

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United State of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pietrzyk, Leslie, 1961–

[Short stories. Selections]

This Angel on My Chest: Stories / Leslie Pietrzyk.

pages ; cm — (Drue Heinz Literature Prize)

ISBN 978-0-8229-4442-3 (hardcover: alk. paper)

I. Title.

PS3566.I428A6 2015

813'.54—dc23

2015025366

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-8109-1 (electronic)

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

Joan Didion, The White Album

Contents

Ten Things

Acquiescence

A Quiz

Heat

In a Dream

One Art

Do You Believe in Ghosts?

Slut

I Am the Widow

One True Thing

Someone in Nebraska

What I Could Buy

Truth-Telling for Adults

Chapter Ten: An Index of Food (Draft)

The Circle

Present Tense

Acknowledgments

TEN THINGS

These are ten things that only you know now:

ONE

He joked that he would die young. You imagined ninety-nine to your hundred. But by “young” he meant sixty-five, fifty-five. What “young” ended up meaning was thirty-five.

In the memory book the funeral home gave you (actually, that you paid for; nothing there was free, not even delivering the flowers to a nursing home the next day, which cost sixty-five dollars, but you were too used up to care), there was a page to record his exact age in years, months, and days. You added hours; you even added minutes, because you had that information. You were there when he had the heart attack.

Now, when thinking about his life, it seemed to you that minutes were so very important. There was that moment in the emergency room when you begged for ten more minutes. You would’ve traded anything, everything, for one more second, for the speck of time it would take to say his name, to hear him say your name.

Later, when you thought about it (because suddenly there was so much time to think; too little time, too much—time was just one more thing you couldn’t make sense of anymore), you wondered why he’d told you he was going to die young. The first time he said it, you punched his arm. “Don’t say that,” you said. “Don’t ever say that again, ever.” But he said it another day and another and lots of days after that. And you punched his shoulder every time, because it was bad luck, bad mental energy, but you knew he’d say it again. You knew then that there would always be one more time for everything.

TWO

He once compared you to an avocado. He was never good at saying what he meant in fancy ways. (You had a boyfriend in college who dedicated poems to you, one of which won a contest in the student literary magazine, but that boyfriend never compared you to anything as simple and real as an avocado.)

You were sitting on the patio in the backyard. It was the day the dog got loose and ran out onto Route 50, and you found him by the side of the road—two legs mangled and blood everywhere—and you pulled off your windbreaker and wrapped the dog in it while your husband stood next to you whispering, “Oh God, oh God,” because there was so much blood. He drove to the vet, catching every red light, while you held the dog close and murmured dog secrets in his ear, feeling his warm blood soak your clothes. And when the vet said she was sorry, that it was too late, you were the one who cupped the dog’s head in both hands while she slipped in the needle, and you were the one who remembered to take off the dog’s collar, unbuckling it slowly and looping it twice around your wrist, and you were the one whose face the dog tried to lick but couldn’t quite reach.

So, that night, out on the patio, the two of you were sitting close, thinking about the dog. It was really too cold to be on the patio, but the dog had loved the backyard; every tree was a personal friend, each squirrel or bird an encroaching enemy. It was just cold enough that you felt him shiver, and he felt you shiver, but neither of you suggested going inside just yet. That’s when he said, “I’ve decided you’re like an avocado.”

You almost didn’t ask why, you were so busy thinking about the dog’s tongue trying to reach your face and failing, even when you leaned right down next to his mouth. But then you asked anyway.

He looked up at the dark sky. “You’re sort of tough on the outside,” he said. “A little intimidating.”

“Maybe,” you said, but you knew he was right. In photos, you always looked as if you didn’t want to be there. Lost tourists never asked you for directions; they asked your husband. It was something you’d become used to and no longer thought about or wondered why anymore.

He continued: “But inside, you’re soft and creamy. Luscious, just like a perfectly ripe avocado. That’s the part of you I get. And underneath that is the hardest, strongest core of anyone I know. Like how you were today at the vet. Like how you are with everything. An avocado.”

At the time, you smiled and mumbled, but could only think about the dog, the poor dog. That was five years ago. What you remember now is not so much the dog’s tongue but being compared to an avocado.

THREE

He predicted a grand slam at a baseball game. It was the Orioles versus the Red Sox, a sellout game up in Baltimore, on a bright, sunny June day, the kind of day when you look out the window and think, Baseball. But in Baltimore it wasn’t possible to go to a game just because it was a sunny day; they were sold out months and months in advance—especially against teams like Boston, which had fans whose fathers had been Red Sox fans, whose kids were Red Sox fans, and whose grandkids would be Red Sox fans. He’d actually bought the tickets way back in December, not knowing what kind of day it would be, and it just happened to be that

perfect kind of baseball day.

He’d grown up listening to games on the radio, sprawled sideways across his bed in the dark listening to A.M. stations from faraway Chicago, New York, St. Louis. He still remembered the call letters and could reel them off like a secret code. Now he brought his radio to the game in Baltimore and balanced it on the armrest between your seats, and the announcers’ voices drifted up in bits and snatches, and part of him was sitting next to you eating a hot dog and cheering and part of him was that child sprawled in the dark listening to distant voices.

The bases were loaded, and Cal Ripken came up to bat. Cal was your favorite player. You’d once seen him pick up a piece of litter that was blowing around the field and tuck it into his back pocket. Something about that impressed you as much as all those consecutive games he’d played.

“What’s Cal going to do?” he asked.

You looked at your score card. (He’d taught you how to keep score; you liked the organization and had developed a special system, with filled-in diamonds for home runs, a K for a strikeout, and squiggly lines to indicate a pitching change.) Cal wasn’t batting especially well lately—the beginnings of a slump, you thought. “Hit into a double play,” you said. Cal had hit into a lot of double plays that season, ended a lot of innings.

He shook his head. “He’s knocking the grand salami”—meaning a home run bringing in all four runners. You’d never seen one in person before.

“Cal doesn’t have many grand slams,” you said—not to be mean (after all, Cal was your favorite player), but because it was true. You knew Cal’s stats, and his grand-slam total was four at the time, after all those years in the majors.

“Well, he’s getting one now,” he said.

After Cal fouled twice for two strikes, you glanced over at him. “It’ll come,” he said.

On the next pitch, Cal whacked the ball all the way across that blue sky.

Everyone stood and cheered and screamed and stomped their feet, and he held the radio in his hand and flung his arm around your shoulders and squeezed tight. From the radio by your ear, you heard the echo of everyone cheering, and you thought about a boy alone in the dark listening to that sound.

FOUR

He was afraid of bugs: outdoor bugs and indoor bugs; bugs big enough to cast shadows and little bugs that could be pieces of lint. Not “afraid” as in running screaming from the room, but “afraid” as in watching TV and pretending not to see the fat cricket in the corner or walking into the bathroom first thing in the morning and ignoring the spider frantically zigzagging across the sink.

“There’s a bug on the wall,” you might say, pointing, hand outstretched, forcing him finally to look up and follow to see where your hand was pointing. You’d repeat: “There’s a bug on the wall.”

Still he’d say nothing.

“Do you see it?” you’d ask.

He’d nod.

So you’d grab a tissue and squish the bug, maybe letting out a sharp sigh, as if you knew you weren’t the one who should be doing this. Or, if it were a big, messy bug like a cricket, you might scoop it up and drop it out the window. Sometimes, if you waited too long, the bug (silverfish, in particular) would scurry into the crack between the wall and carpet, and you’d imagine it reemerging in the future: bigger, stronger, braver, meaner. Bugs in the bathtub were easiest, because you could run water and wash them down the drain. You learned many different ways to get rid of bugs.

He never said, “Thank you for killing the bugs.” He never said that he was afraid of bugs. You never accused him of being afraid of bugs.

FIVE

He kept his books separate from yours. Certain shelves on certain bookcases were his; others were yours.

Maybe it made sense when you were living together, before you were married. If one of you had to move out, it would only be a matter of scooping armloads of books off the shelves, rather than sorting through, picking over each volume, having to think. It would allow you to get out fast. Plus, with separate shelves, he could stare at his long, tidy line of hardcovers, undisturbed by the scandalous disarray of your used paperbacks. He liked to stare at his books with his head cocked to the right—not necessarily reading the titles, just staring at the shelf of books, at their length and breadth and bulk. You never knew what he was thinking when he did this.

After your wedding, when you moved into the new house, you said something about combining the books, maybe putting all the novels in one place and all the history books in another and all the travel books together and so on, like that.

He was looking out the window at the new backyard, at the grass no one had cut for weeks and weeks. Finally, he said, “We own every last damn blade of grass.”

“What about the books?” you asked. You were trying to get some unpacking done. There were boxes everywhere. The only way to walk through rooms was to wind along narrow paths between stacked boxes. There were built-in bookcases in the living room by the fireplace—two features the realtor had mentioned again and again, as if she knew that you were imagining sitting in front of a fire, reading books, sipping wine, letting the machine take the calls. As if she knew exactly the kind of life you had planned.

“I’ll do the books,” he said. But he didn’t step away from the window.

It was a nice backyard, with a brick patio, and when you’d stood out there for the first time, during the open house, you’d thought about summer nights with the baseball game on the radio and the coals dying down in the grill and the lingering scent of medium-rare steak and a couple of stars squeezing through the glare of the city to find the two of you.

Again you offered to do the books; you wanted to do the books. You wanted all those books organized on the shelves; his and yours, yours and his.

“I never thought I’d own anything I couldn’t pack into a car,” he said.

You felt so bad you started to cry, certain only you wanted the house, only you wanted the wedding. “Is it so awful?” you asked.

He reached over some boxes to touch your arm. “No, it’s not awful at all,” he said, and it turned out that this was what you really wanted—not the patio, not the built-in shelves next to the fireplace, not the grass in the backyard, but the touch of his hand on your arm.

You did the books together, and suddenly something about keeping them separate felt right, as if now you realized that the books would be fine on separate shelves of the same bookcase, in the house you’d bought for the life you had.

SIX

He once saw a ghost. He was mowing the lawn in front, and you were in back clipping the honeysuckle that grew over the fence. Your neighbor—an original owner who’d bought his house for seven thousand dollars in 1959—wanted to spray kerosene and set the vines on fire, but you said no. You liked the smell of honeysuckle on June nights. You liked the hummingbirds flitting among the flowers in August. You even liked all that clipping, letting your mind go blank as you wrestled with the vines, cutting and tugging, yanking and twisting and pulling—knowing that whatever you cut would grow back by the end of the summer, that in the end the honeysuckle would always come back, maybe even if your neighbor burned down the vines.

It was that time of the early evening when the shadows were long and cool and the dew was rising on the grass; that time when, as a barefoot child, you would start getting damp toes. You half heard the lawn mower whining back and forth, back and forth, and you were thinking ahead to sitting on the patio and watching the fireflies float up out of the long, weedy grass under the apple tree. Then the lawn mower stopped abruptly; it needed more gas, you thought, or maybe there was a plastic bag in the way. When the silence lingered, you walked around to the front yard, curious, and found him leaning up against the car in the driveway, the silent lawn mower in front of him. The streetlight flicked on as you reached him; he held out his arms for a hug, and you felt his sweat, tacky against your skin.

“I saw a ghost,” he said.

You pushed the hair back from his forehead and bl

ew lightly on it to cool him down. His forehead was pale compared to the rest of his face.

He pointed over toward the big maple tree, the one that was so pretty each autumn. But nothing was there.

“What kind of ghost?” you asked. You still had your hand on top of his head, and when you removed it, his hair stayed back where you’d pushed it.

“Like a soldier from the Civil War,” he said. “He was leaning against that tree, and then he was gone.”

“Confederate or Union?” you asked.

He looked annoyed, as if you’d asked the wrong thing, but it seemed a logical question.

“It was a ghost,” he said. “I saw a ghost.”

“Did he do anything?”

“Maybe it was the heat,” he said.

“Maybe it was a real ghost,” you said. “Confederate encampments were along here.” There was a silence. A car went by too fast, music spilling from its open window. “That tree’s big enough to have been here then.”

“This is stupid,” he said, and he leaned down and pulled the cord on the lawn mower. The engine roared, and he couldn’t hear you anymore, and you watched him push the mower across the yard. You saw nothing under the maple tree, just newly cut grass spit into lines and shadows stretching slowly into the dark.

Now you’re the one who cuts the grass. People tell you to hire a service, but you don’t. When you’re done mowing in the evening, you lean against the car and wait, but all you ever see are fireflies rising from the damp grass where you leave it long under the maple tree.

SEVEN

When he ate malted milk balls, he sucked the chocolate off first. Thinking you weren’t watching, he’d roll the candies from one side of his mouth to the other, making the sort of tiny noises you’d imagine a chipmunk would make, or a small bird, or something else tiny and cute. If he caught you watching him, he’d instantly stop. Sometimes, just to tease, you’d ask a question to make him talk, and his words would come out lumpy and garbled, pushed around the sides of the candy. “What?” you’d say, still teasing. “I don’t understand.” But no matter how much you teased, he never chewed.

This Angel on My Chest

This Angel on My Chest